"By Law Vest"

What does it take to vest appointment power in Secretary Kennedy?

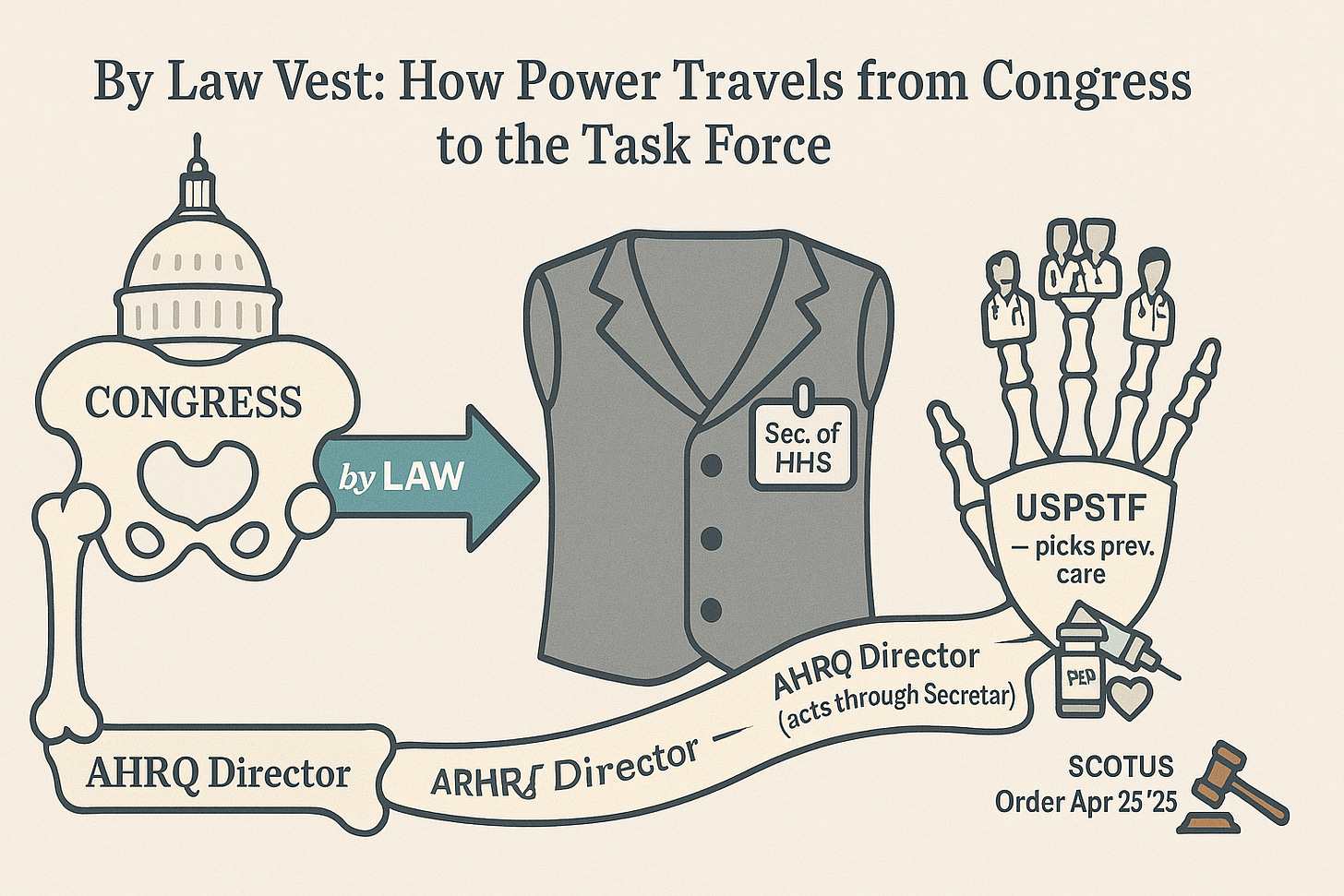

On Friday, the Supreme Court issued an order for supplemental briefing in Kennedy v. Braidwood Management. The parties will now address whether Congress has vested in the Secretary of Health and Human Services the authority to appoint members of the Preventive Services Task Force. In this post, I’ll try to explain what the order is about, why it’s probably good news for the government, and how I think the matter should be resolved.

The Background

Braidwood is about a part of the Affordable Care Act that tries to nudge people to get preventive care. Specifically, the ACA says that employers and insurers must cover, at no cost to the patient, all top-rated preventive care specified in “recommendations” issued by the Preventive Services Task Force, an advisory body in HHS.

The Task Force has recommended the use of drugs that prevent the spread of HIV between sexual partners, known as pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP, in certain high-risk populations. Because Braidwood dislikes having to cover PrEP, as well as other preventive services, it sued on the ground that vesting authority to issue binding recommendations in Task Force members violates the Appointments Clause.

The Supreme Court heard the Appointments Clause challenge last Monday. Going in, the government had conceded that Task Force members were “officers of the United States” and thus subject to the Appointments Clause. Coming out, it was apparent that the justices did not buy Braidwood’s argument that Task Force members are principal officers.

The consensus, instead, was that Task Force members are inferior officers, as the government had argued. The Appointments Clause thus allows them to be appointed by a department head—here, the Secretary of Health and Human Services—but only if “the Congress” has “by Law vest[ed]” that authority in him. Some of the justices weren’t sure if Congress had done so. The Fifth Circuit didn’t pass on the question because it held that Task Force members were principal officers. Braidwood’s lawyer, Jonathan Mitchell, pushed hard for a remand to the Fifth Circuit to decide that question in the first instance.

Friday’s order declined that invitation for now and instead asked for further briefing. That’s good news for the government, and suggests that a majority of the justices may be reluctant to give the Fifth Circuit, which has been sympathetic to Mitchell’s claims, another chance to throw a constitutional wrench into the works.

The Arguments

What law, according to the government, gives the Secretary the power to appoint Task Force members? Under 42 U.S.C. §299(a), the HHS Secretary is instructed to “carry out” the functions of an HHS subagency called the Agency for Health Research and Quality, or AHRQ, by “acting through [its] Director.” In addition, Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1966, which Congress adopted into law,1 gave the Secretary the power to perform “all functions of the Public Health Service,” which includes both AHRQ and the Task Force.

Pair that with 42 U.S.C. §299b-4(a)(1), where Congress told the AHRQ director to “convene” the Task Force. As the government sees it, AHRQ’s powers, including the power to “convene” the Task Force, just are the Secretary’s powers. As a result, Congress has “by Law vest[ed]” the convening authority—which is to say, the appointment power—in a “Head of Department.”

The argument is a little indirect but I think it works. To see why, consider the goals that the “by Law vest” language in the Appointments Clause is meant to serve. First, it protects Congress’s prerogative to specify when it means to deviate from the default rule of presidential appointment backed by Senate approval. Second, it guarantees clear lines of authority by requiring Congress to deposit the appointment power only on specified individuals or entities—the President, the courts, or department heads.

Achieving those goals doesn’t require Congress to use magic words (“We hereby vest appointment authority in the Secretary”). It just requires a law that, fairly read, deviates from the default and specifies who ought to do the appointing. We have that here.

During oral argument, Mitchell claimed that Congress never specified the appointing officer. “Anyone can appoint under the statute. The Secretary of Energy could appoint. The president could appoint. The AHRQ director could appoint. Someone from the private sector could appoint. The statute doesn't say anything at all about who appoints. No one is vested with the authority because the statute takes no position on who appoints.”

That’s an awfully stingy reading of a law that allows the Secretary, working through AHRQ, to “convene” the Task Force. What work is “convene” doing if not vesting appointment authority? The power to pick the dates for Task Force meetings? To choose the seating arrangements? I don’t take the Supreme Court to be so committed to Appointments Clause formalism that it will insist on something more explicit. What would be the point? And at any rate, the law should be read to avoid constitutional problems, not invite them.

The Homework

The Supreme Court’s order asked the parties to address two cases. The first is United States v. Hartwell (1868), where the Court held that a Boston clerk accused of defrauding the U.S. Treasury was an officer of the United States. The clerk had been appointed, the Court said, pursuant to a law that “authorized the assistant treasurer, at Boston, with the approbation of the Secretary of the Treasury, to appoint a specified number of clerks, who were to receive, respectively, the salaries thereby prescribed.”

The Task Force is convened in a similar way. Appointment authority is nominally vested in an inferior officer, subject to direction by a department head. Hartwell says that’s fine. Mitchell claims that Hartwell is not on point because “the statute required the Secretary of the Treasury to approve any appointments made by the assistant treasurer.” But the statute here outright gives AHRQ’s powers to the HHS Secretary—not just the power to approve, but the power to appoint in the first instance. That’s more power than the Treasury Secretary had in Hartwell, not less.

The second is United States v. Smith (1888), where the Supreme Court held that different Treasury Department clerks were not officers of the United States. The reason was that “their appointment is not made by the Secretary, nor is his approval thereof required.” The Court distinguished the case from Hartwell as follows:

[Hartwell’s] appointment by [the assistant treasurer] under the act of Congress could only be made with the approbation of the Secretary of the Treasury. This fact, in the opinion of the court, rendered his appointment one by the head of the department within the constitutional provision upon the subject of the appointing power. The necessity of the Secretary’s approbation to the appointment distinguishes that case essentially from the one at the bar. The Secretary, as already said, is not invested with the selection of the clerks of the collector; nor is their selection in any way dependent upon his approbation.

Smith works to the government’s benefit too. The clerk would have been an officer of the United States, the Court said, if the Secretary had been “invested with the selection of the clerks of the collector.” The Secretary here has been so invested with the selection of the Task Force members. That ought to be enough to satisfy the Appointments Clause.

This is my first sole-authored post for Divided Argument. More to come, and thanks to Dan and Will for the invitation to become a regular contributor.

Correction: Reorganization Plan No. 3 was submitted to Congress and took effect because Congress did not object within the requisite time. In 1984, to cure any problems that might have arisen from the Supreme Court’s decision in INS v. Chada, Congress adopted a law that “ratifies and affirms as law each reorganization that has [previously] been implemented,” including Reorganization Plan No. 3. Josh Blackman and Seth Barrett Tillman flagged the point here. They also offer an elaborate (and, in my view, unpersuasive) explanation for why the reorganization plan still doesn’t confer the requisite authority on the HHS Secretary.