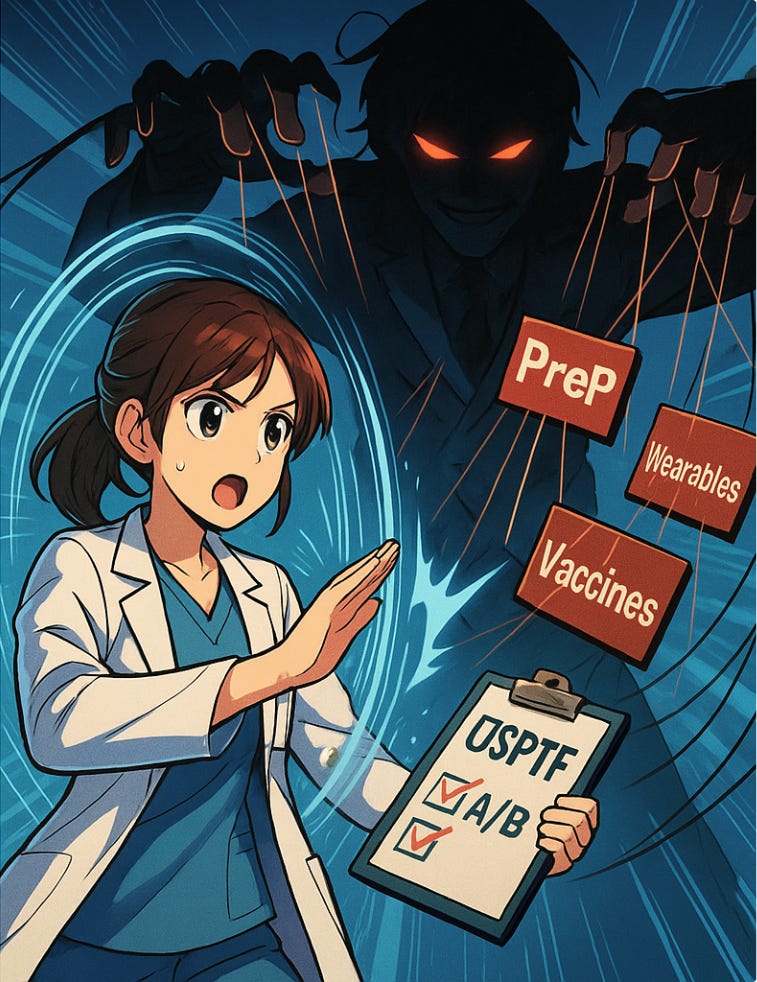

Less PrEP, More Fitbits?

What Braidwood means for the future of preventive care

One of the ironies of Kennedy v. Braidwood Management is that it was originally pitched as a fight over the requirement to cover pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, which prevents the transmission of HIV.1 The lead plaintiff, Braidwood Management, objected to PrEP because it “facilitate[s] behaviors such as homosexual sodomy, prostitution, and intravenous drug use—all of which are contrary to [the owner’s] sincere religious beliefs.”

Yet PrEP gets only a brief, footnoted mention in the Supreme Court’s opinion. Early in the litigation, Braidwood had won an exemption from the PrEP coverage mandate under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. (The Biden administration did not appeal.) Braidwood could still press its Appointments Clause challenge to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) because it also objected to covering other preventive services. But it wasn’t clear (to me, anyhow) that its heart was really in the argument.

So by the time the Supreme Court heard the case, PrEP wasn’t an issue, at least as to Braidwood. And then Braidwood lost its Appointments Clause challenge, meaning that the body’s recommendations are, in fact, binding. You’d think PrEP coverage would be safe.

But maybe not. I’ve got a new piece at The New England Journal of Medicine puzzling over what comes next.

Braidwood confirms that binding USPSTF recommendations are constitutional only because the HHS secretary can exercise strong control over the task force. How Secretary Kennedy will use that authority remains to be seen. He recently dismissed all 17 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, another federal panel of experts, and replaced them with several vaccine skeptics. Braidwood gives him clear authority to similarly reshape the USPSTF. Indeed, Kennedy has already cancelled a scheduled July 10 meeting of the USPSTF, prompting speculation that he may be poised to fire its members.

Nonetheless, he may choose to do little. Preventive services aren’t as politically controversial as vaccines, and preventive care is a cornerstone of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement. In addition, Braidwood is clear that the HHS secretary does not have the power to adopt legally binding recommendations without first securing the USPSTF’s approval. Kennedy’s power will therefore be limited by what the USPSTF is willing to endorse.

Under Kennedy’s authority, however, the task force may be less willing to recommend politically sensitive types of preventive care, including care targeting sexually transmitted infections. In addition, Kennedy could push the USPSTF to withdraw the PrEP recommendation. He has already eliminated or reassigned staff from the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. When asked during his confirmation hearings whether he would ensure coverage for PrEP, he did not give a definitive answer.

Kennedy may also come to see the USPSTF as a vehicle for guaranteeing coverage of medical care of dubious value. In June 2025, he testified to a congressional committee about his support for wearable devices that monitor blood glucose levels, including for people without diabetes. “My vision is that every American is wearing a wearable within 4 years,” he said, noting that HHS is exploring ways of ensuring that the cost of wearables “can be paid for.” One way to cover those costs would be to instruct USPSTF members to give an “A” or “B” rating to the use of qualifying wearables — a decision that would inflate the price of health insurance for all Americans. If task force members refuse to adopt such a rating, they could be dismissed and replaced by members who will.

So a case that was about PrEP turned into a case that was about every preventive service except PrEP—only to become, in a roundabout way, a case about PrEP again. And maybe also wearables. It’s wild.

To be more precise, that’s how the portion of the case challenging the authority of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force was pitched. Other plaintiffs challenged the authority of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Health Resources and Services Administration, but those challenges weren’t at issue in the Supreme Court case.