Trump 2.0 and the Supreme Court Reform Debate

Does the left's turn to the courts in response to the Second Trump Administration's excesses show advocates of structural reform of the Supreme Court were wrong?

For a bit less than a decade, there’s been a robust debate about structural reform of the Supreme Court. I’m not sure when you might say that the debate really got going—the circumstances of the Garland/Gorsuch nominations may have set things off, but things really started raging after Justice Kavanaugh replaced Justice Kennedy.

I’ve been an active participant in that debate, starting in my 2019 article “How to Save the Supreme Court” with Ganesh Sitaraman and various follow-on pieces about reforms like term limits, Court-packing, and jurisdiction-stripping.

I’ve never had any illusions that structural reform of the Supreme Court was likely to happen at any point in my lifetime. I think debates about reform of the Court are still worth having, but I don’t need to press that point in this post. In any event, structural Court reform was essentially certain not to happen during this or any other Republican Administration—or, really, any period without Democratic control of the Presidency and both Houses of Congress. That makes the Supreme Court reform debate practically irrelevant in the short term.

But one refrain I’ve heard recently from conservatives is that current events show how wrong critics of the Court on the left have been. That is, the argument goes, as the Administration breaks the law over and over in numerous ways, and with Congress having entirely abdicated its responsibility to check the Executive Branch, the courts are the only thing standing in the way of full-on authoritarianism.

Over recent years, conservative defenders of the Court have said that much of the criticism of the Court motivating reformers is baseless and even dangerous; for these critics, what’s happening today presents the ultimate gotcha moment, showing how wrong the critics have been.

Here, as a Court critic who is at least an incidental target of this argument, I want to respond. Does the role of the judiciary—and the left’s turn to the courts—in the Second Trump Administration show that the critics and would-be reformers were wrong?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, my answer is “no”—or, at least, a partial one. Here’s why.

My first response is that it is far from clear so far whether the premise of this critique is true. As Will recounted a few weeks back, the Court’s approach to the new Administration on the emergency docket is mixed so far. Using Will’s framing, it’s not clear yet what “model” the Court is going to follow. It’s at least possible that the Court will end up not being a meaningful check on the Trump Administration’s lawlessness at all. In that case, the most strident critics of the Court on the left may well be proven right.

I don’t expect that to happen, though—I do expect the Court to push back in some areas (even though I don’t expect the Court to push back on every illegal thing the Administration is going to do—another topic for a future post). Even so, I don’t think that in any way proves that arguments for reform were wrongheaded (at least my arguments).

In How to Save the Supreme Court, Sitaraman and I argued that the Court needed “saving” precisely because having an independent judiciary with some form of power of judicial review was important:

The reason that a change to the Court’s structure and the Justices’ selection method was needed, we argued, so that we could build a Court that commands respect from as much of our country as possible. If you think it’s important for the Court to push back on political actors some of the time, you should want a Court that has some credibility across the political spectrum. And for many reasons, our selection system is breaking down in ways that really threaten the court’s credibility with half the country.

The specific causes of this that I discuss in another piece, Non-Partisan Supreme Court Reform and the Biden Commission, explained what I see as the developments producing the current breakdown:

Life tenure, plus the increasing lifespan of Justices, plus a small Court, make vacancies rare. And unpredictable, as they are a product of the combination of deaths and strategic retirements. That has led to a wildly lopsided number of appointments between the two political parties over the last half century or so.

Increased polarization in both our political and legal cultures, creating a significant divergence between the kinds of justices that the two political parties put on the bench.

A powerful Court, that is expected to and does weigh in on the weightiest political issues of the day.

This all makes appointments to the Court extremely consequential, and creates incentives for the kinds of destructive gamesmanship we saw during the Obama and first Trump administration. And, I argue, the arbitrariness and perceived unfairness of the ways in which seats on the Court are politically distributed is undermining the Court’s perceived legitimacy among Democrats and people on the left—a good chunk of the country. That, Ganesh and I argued, presents a long-term danger to the rule of law. We thus promised reforms that in our view would distribute power over the Court more fairly, and would diminish opportunities for destructive gamesmanship.

One can criticize our proposed solutions—there are plenty of potential objections. (For some particularly strong ones, see the response by co-blogger Steve Sachs). It’s quite possible that there’s no way to reform the Court without creating a legitimacy problem with one side of the country or another; perhaps reforms that would satisfy the left would destroy the Court’s legitimacy with the right, and so on. I don’t want to relitigate those questions right now.

My point here is that, if you buy the premise that a legitimate Court that can sometimes stand up to the political branches is an important feature of our constitutional system, present events only reinforce the arguments I’ve made for reform. That’s because this Court, to the extent that it is and will stand up to the Trump Administration, is able to do so in part because it has credibility with the President’s own party. This Court’s conservative credentials are pretty unimpeachable (notwithstanding grousing by some of the usual suspects). A court composed of six Democrats would be a lot easier for Trump to ignore.

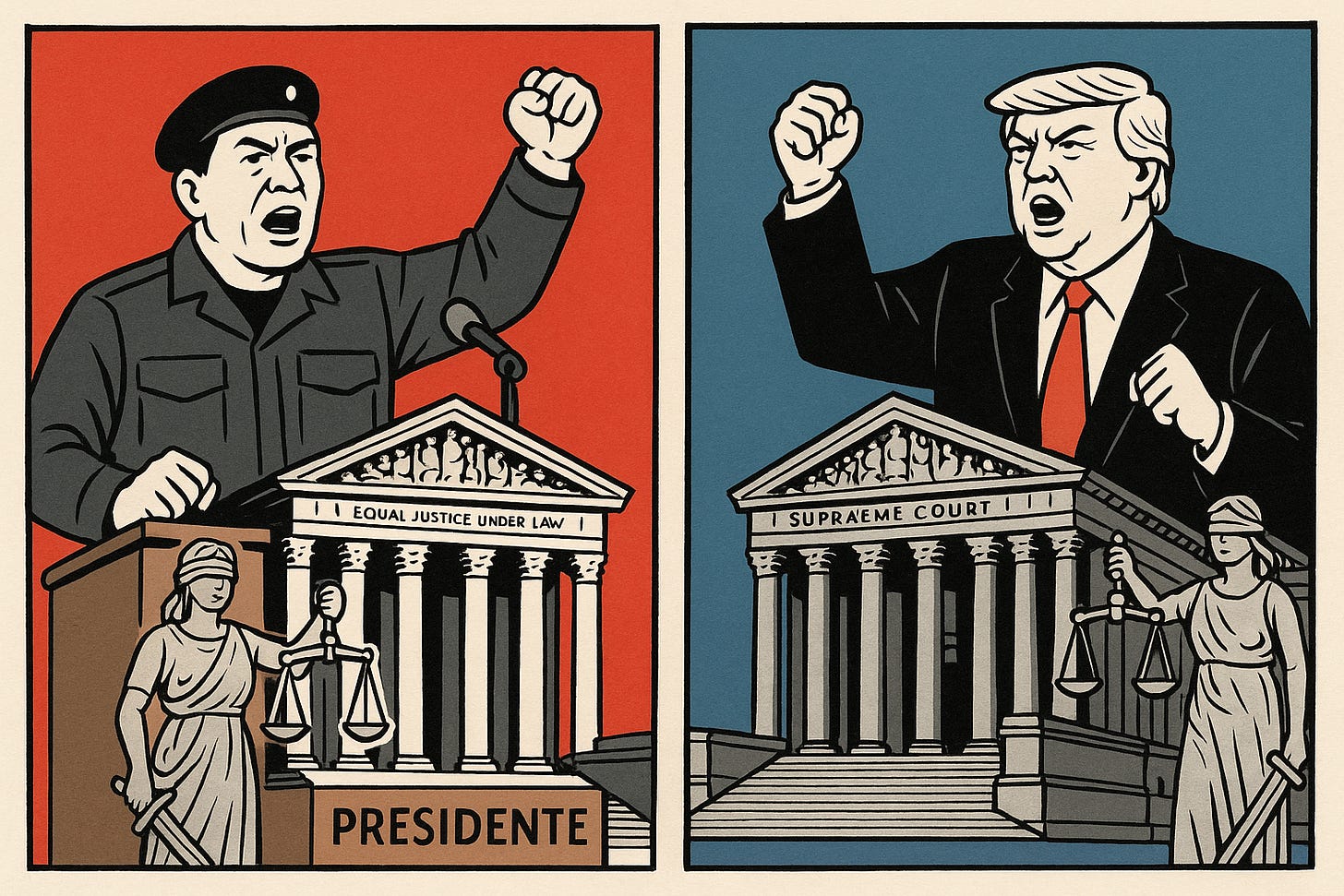

But by the same token, imagine if things were flipped. What would happen if this Court was trying to stand up to an authoritarian left-wing president who had just been elected? (Imagine, say, an American Hugo Chavez). Given the Court’s legitimacy challenges with the left, it’s far from clear that this Court would be well-positioned to rein in such a President’s excesses. If you want a Court that can provide some check against authoritarianism dangers—wherever they come from—you should want a Court that has a broad basis of legitimacy across the political spectrum. I don’t think we have that right now—or, at least, the Court has less of the legitimacy that it might need than it did a generation, or even a decade, ago.

Maybe building a Court that has such broad legitimacy is impossible. If it’s not, though, that’s what we should aspire to. And that’s what I’ve argued for in my scholarship on Supreme Court reform.

I do think, though, that present events pose a major challenge to folks who have argued for disempowering the Court—taking the Court out of the political equation entirely through reforms that would cripple its ability to overrule the elected branches. If Democrats had somehow managed to do that a few years ago, and we were in the same situation we are now, things would be a lot worse for anyone who isn’t firmly committed to Trumpism.

Although robust judicial review has costs, those costs are in my view worth paying if the Court can actually prevent, or at least slow down, a slide into full-on authoritarianism. This Court isn’t perfect, but right now it looks like the only institution with any power that is willing to try to do that. For now, as much as I might wish for a better Court, I’ll take it.