Things to Read This Week (8/25)

International Law, Thunder Basin, and the Unitary Executive

I’m digging out of a pile of obligations that arrived during my vacation hence the late post.

Extradition in the Early Republic: International Law and Constitutional Authority, by my colleague Curt Bradley. A fascinating discussion of the early practice and legal basis of U.S. extradition practice, with perhaps important methodological payoffs too: “This regime, the Article argues, emerged not from appeals to the constitutional text or original understandings, but rather from structural intuitions, consequentialist considerations, and, as time went on, historical traditions. As the Article further documents, the constitutional law of extradition had a relational interaction with international law, in that the views of U.S. interpreters concerning the nation’s international law duties were relevant to their views of constitutional authority, and vice versa.”

Mike Ramsey responds, “Assume it's true, as the abstract declares and the article argues, that the post-ratification approach to extradition ‘emerged not from appeals to the constitutional text or original understandings, but rather from structural intuitions, consequentialist considerations, and, as time went on, historical traditions.’ Consistent with his broader approach to constitutional interpretation, Professor Bradley clearly thinks these post-ratification developments should be influential in modern interpretation. But my question is, isn't the opposite true for originalists? That is, if post-ratification political actors in fact embraced intuition and consequentialist considerations rather than text and original understanding, isn't that a reason for originalists to sharply discount post-ratification practice? Post-ratification practice is relevant to original meaning only if post-ratification actors were trying to discern and be guided by original meaning. If they weren't, why do we, as originalist interpreters, care what they did?”

Perhaps I am the man with a hammer to whom everything looks like a nail, but I think there is probably a third way to bridge this debate — by recognizing that founding-era constitutional law, much of which was reflected in practice shortly after ratification, included a healthy dose of non-textualist reasoning, including appeals to unwritten law such as international law. If this was the law not just after the Founding but at the Founding, as I think it was, it would be just as worthy of the label “originalism.” For more, see Baude and Sachs, Yes, the Founders were Originalists.

Bypassing Agency Adjudication, by another UChicago colleague Brian Lipshutz: “This Article examines the contested practice of bypassing agency adjudication to accelerate judicial review of non-final executive action. . . . Traditionally, such ‘ultra vires’ review required a clearly unlawful action and an inadequate administrative remedy. But modern courts further limit it by applying three judicially developed timing doctrines—exhaustion, ripeness, and Thunder Basin.

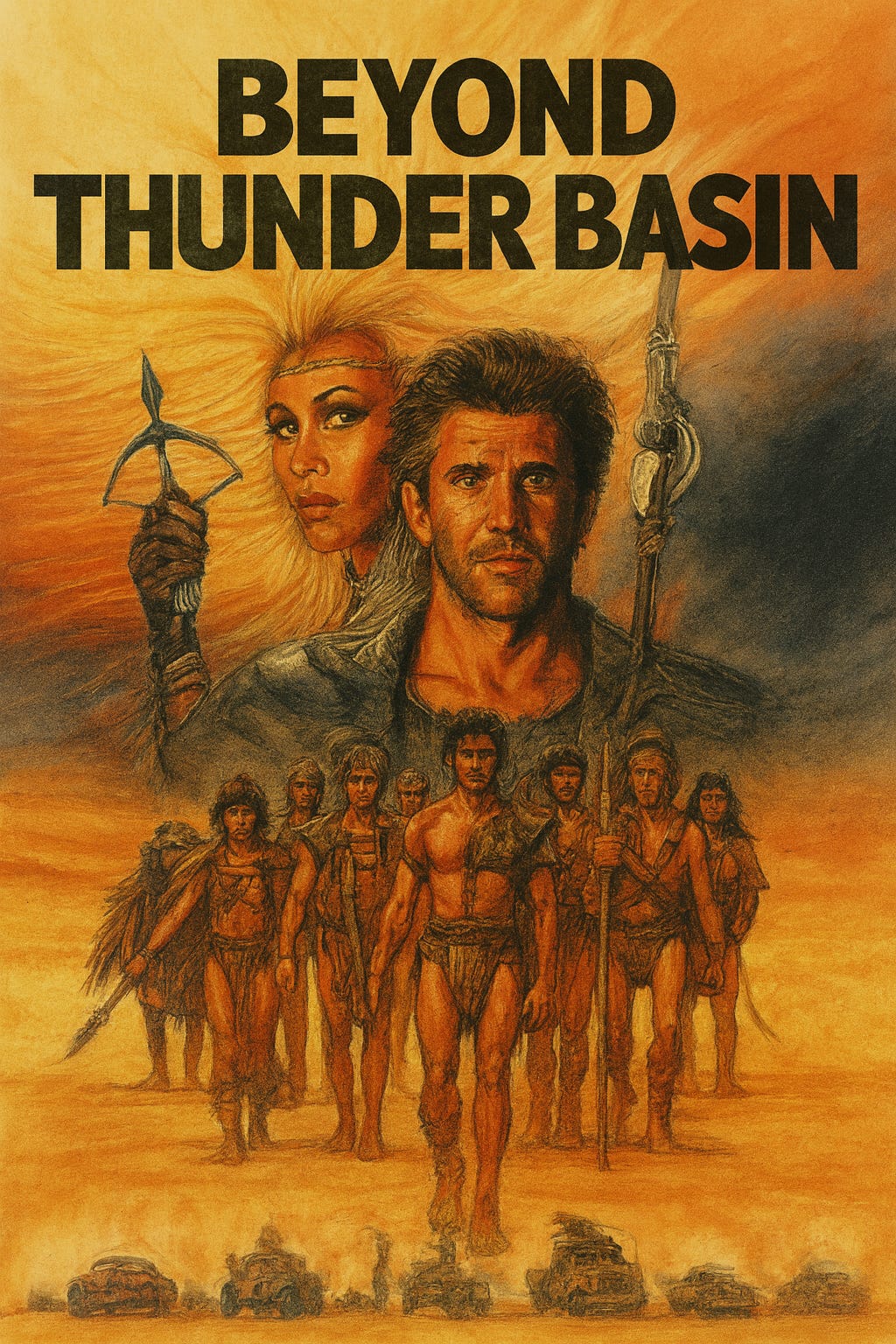

This Article explains why the traditional ultra vires model—without the timing doctrines—should govern the bypassing of agency adjudication.” (Brian wisely avoided what for me would have been a strong temptation to call the article “Beyond Thunder Basin.”)These blog posts by Rick Pildes (“The Roberts Court Has Applied the Unitary Executive Branch Doctrine Consistently Across Administrations”) and Jack Goldsmith (“Nonsense and Sense About Supreme Court Interim Orders”). I will add them to my Realistic Legal Realism files — it’s important that realist critiques of the Court actually be accurate and realistic.

Additionally, another insightful blog post, Moderating the Unitary Executive Branch in Kennedy v. Braidwood Management, by Zach Price at J.Reg. Notice and Comment.

Prof. Goldsmith's post is a must-read.