Things to Read This Week (7/28)

The HLR Foreword and much much more.

An embarrassment of riches this week.

Richard Re has posted a draft of his Harvard Law Review Foreword: To A Conservative Warren Court: “Ideological conflict has masked an underlying continuity in the American legal system. In recent years, the Supreme Court -- while obviously subject to fierce criticism -- has been doing its part to preserve the rule of law, as distinct from partisan politics. That was true in the Warren Court era and remains true today.” Likely to provoke disagreement on both the left and right, an important and terrific piece.

And by another author of this blog, The Practice of Executive Constitutionalism, by Conor Clarke and Dan Epps: “a thick account of Executive Branch constitutional interpretation, particularly in its centralized form controlled by the President and the Department of Justice. . . . [A] rich understanding of how Executive Branch constitutional interpretation has worked is critical for assessing the virtues and vices of executive constitutionalism writ large—especially in the second Trump Administration, in which expansive claims of constitutional authority loom large.”

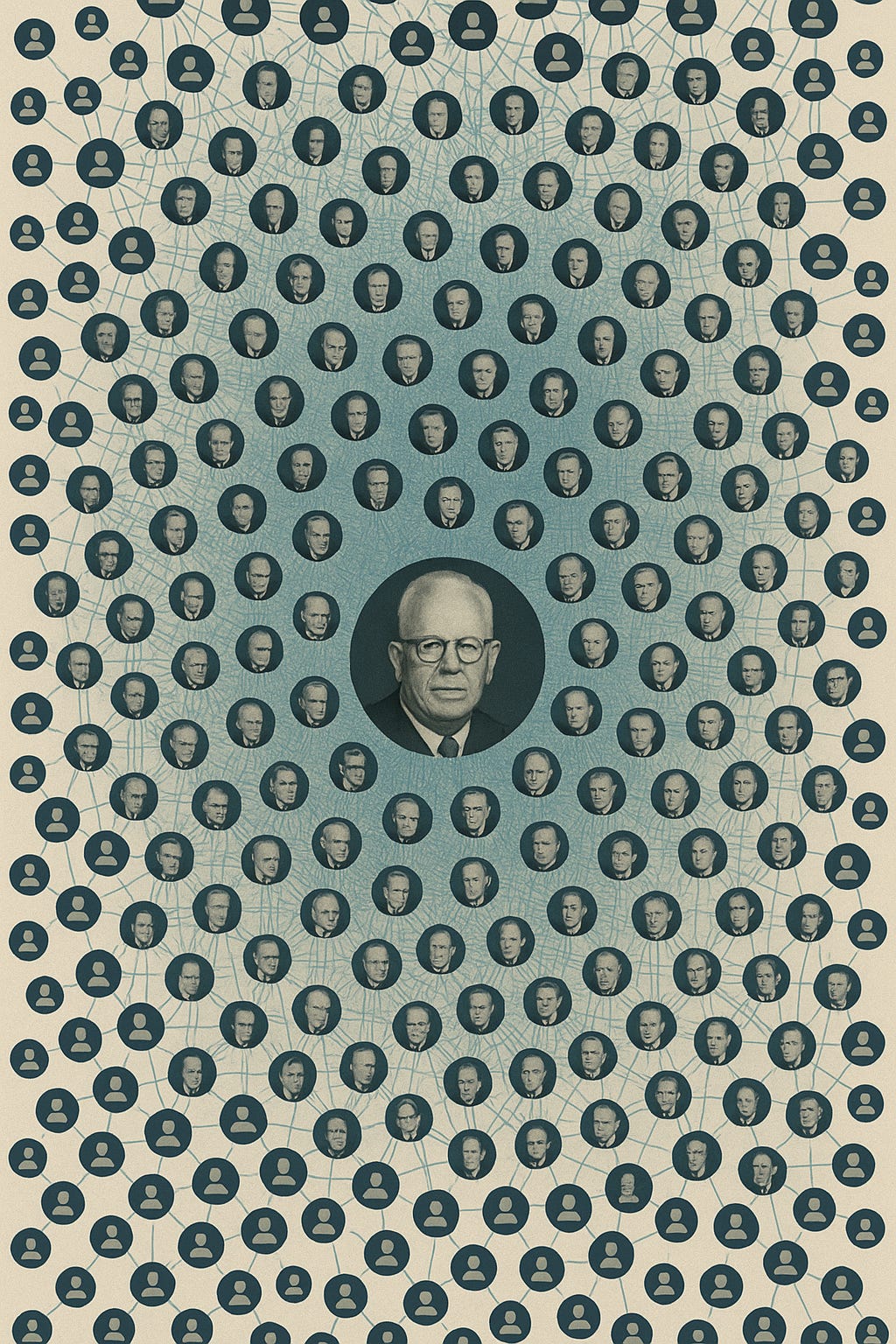

Julian Nyarko and David Pozen, Social Media Participation and Scholarly Success in Law, finding that “joining Twitter increases citation counts by an average of 22% per year and improves article placements by up to 10 ranks for law professors.” I don’t have the chops to judge whether the “synthetic controls” used by the article are convincing, but as a matter of common sense doesn’t this result kind of have to be true? But before we turn the article into a referendum on Twitter and other social media sites, I’d be curious about the effect of other activities like “placing your articles on SSRN,” or “presenting your piece at workshops and conferences” or “giving your pieces good titles” or “sending out reprints to strangers.” All activities that involve showing your piece to new people seem likely, in the aggregate, to increase readers and therefore citations. And presumably that is fine?

Josh Chafetz, The Chadha Presidency. (“The Trump presidency is characterized to a unique degree by the rise of affective polarization, policy unorthodoxies, and a disdain for political norms. Each of these factors suggests that a binding legislative veto would be even more significant in the Trump presidency than in prior presidencies—or, seen from the other direction, they suggest that Chadha’s destruction of the legislative veto has had its most significant ramifications in the Trump presidency.”)

The Removal Question: A Timeline and Summary of the Legal Arguments, an adversarial collaboration from Aditya Bamzai and Peter Shane. Kudos to Diego Zambrano and the Stanford Law Review for investing in the genre of adversarial collaboration, we need more of them and this one is great. And kudos to the authors for careful patient engagement on a polarized topic. (Ahem.)

Severability and Liberty, by Randy Kozel in the American Journal of Jurisprudence. Short and self-recommending, an argument against the presumption of severability when liberty is at stake.

The Curiously Minor Role of Minor v. Happersett, by Susan Appleton, Travis Crum, and Hannah Keidan — foreword to a forthcoming symposium on the 150th anniversary of the case (denying a woman’s claimed right to vote under the 14th Amendment Privileges or Immunities Clause). As a point of personal privilege, I note that they note that one of the few casebooks to excerpt Minor is Paulsen, McConnell, Bray, and Baude.

Link to Josh's Chadha piece should be fixed!

Scholars like to say that they offer a "rich" understanding of something (which makes sense because they worked and thought hard on it). But is it ever the case that scholars conceive their work as "non-rich", "light" or similar?