The House Judiciary Committee Moves to Restrict Contempt Enforcement

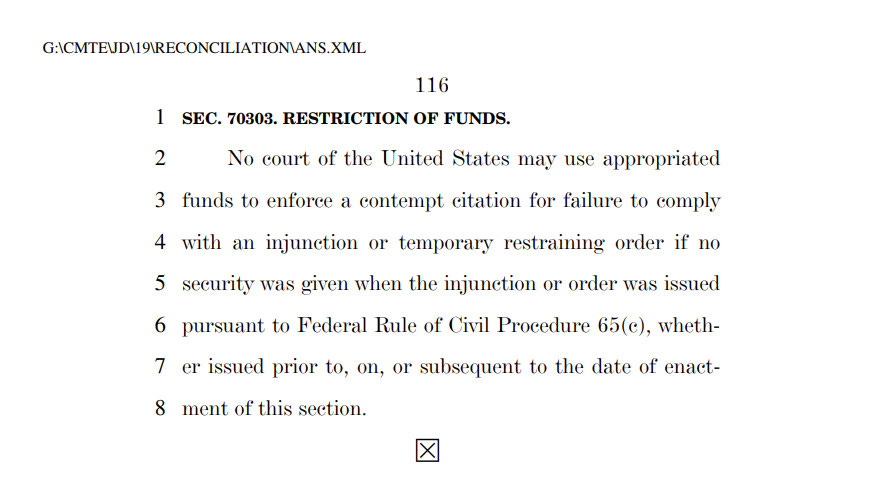

Tonight the House Judiciary Committee released its reconciliation bill, and it includes a provision (h/t Courtney Buble) that purports to restrict the power of the federal courts to enforce their injunctions and temporary restraining orders with contempt:

Right now, federal courts usually do not require security before granting a preliminary injunction—and almost never do when a suit is brought against a government defendant. (You can find empirical support for that proposition in Preliminary Injunction Realism.) That practice is contrary to Federal Rule 65(c), but a court’s failure to require security does not invalidate the injunction itself. (The same is true of the other requirements of Rule 65: if an injunction cross-references the complaint to provide some of the injunction’s content, that is a failure to follow Rule 65(d)(1)(C), but it does not follow that the defendant is free to violate the injunction with impunity.)

I support the broader use of injunction bonds when courts grant preliminary injunctions, and I’ve written about that in The Purpose of the Preliminary Injunction. Broader use of injunction bonds would have a number of advantages, including that they would give weight to the government’s regulatory interests and they would encourage a better fit between the scope of the injunction and the interests of the plaintiffs. (For a thoughtful critique, see Injunctive Restraint by Cassandra Burke Robertson.)

But the House Judiciary Committee’s bill is underinclusive, overinclusive, and likely unconstitutional.

Let’s start with underinclusive. The restriction in this bill is the easiest thing in the world to get around going forward: for a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order in the future, all the bond has to be set for is $1. Which means that for these kinds of interim orders, the bill is not genuinely prospective legislation at all, but is instead an attempt to immunize defendants from contempt when they disobey previously granted preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders.

The bill is also grossly overinclusive, because nothing in this section is restricted to federal defendants. That means in every case in which a federal court has previously issued an injunction—whether it’s a school desegregation injunction that’s still on the books to an antitrust injunction against a tech company to an injunction against patent infringement in a suit between two private parties—it would now be open season for violations without any possibility of contempt enforcement. If that’s intended, it’s an evisceration of the results of the judicial process over decades.

The bill is also overinclusive because it extends to all injunctions, and not just preliminary ones. Even though the requirement is often honored in the breach, injunction bonds are required by Federal Rule 65(c) for preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders, but not for final injunctions. That means the bill would eliminate contempt enforcement for final injunctions. I cannot tell whether this is by design or just poor drafting. A court may be able to get around this in the future by requiring a litigant who obtains a final injunction to give security (after all, equitable relief can always be conditioned—those who would have equity must do equity). But that would be a significant change from current practice, and it is hard to see any reason for such a change other than trying to limit the effects of this bill.

Finally, the bill is probably unconstitutional as an attempt to interfere with the inherent power of a court of equity to enforce its decrees with contempt. In Michaelson v. U. S. ex rel. Chicago, St. P., M. & O. Ry. Co., 266 U.S. 42 (1924), the Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of a statute that required jury trials in contempt proceedings. The key passage is pages 63-67. The Court construed the statute as applying only to prosecutions for criminal contempt, and not to summary contempt enforcement (e.g., a disturbance in a courtroom) or civil contempt enforcement (whether coercive or compensatory), since if the statute applied to those cases there would be a serious question about its constitutionality. A statute that required jury trials in civil contempt cases, the Court thought, would be in serious tension with the inherent power of a court of equity to enforce its decrees. And the statute in Michaelson merely added process (specifically a jury); it did not eliminate the ability for the court to enforce its decrees with either civil or criminal contempt.

True, the Court did not actually hold that the statute in Michaelson would be unconstitutional if applied outside of criminal contempt prosecutions, but it certainly suggested as much. And if such a statute were unconstitutional, then a fortiori the House Judiciary Committee’s bill would be unconstitutional. I do not see how it can be read as limited to criminal contempt. Nor does it merely add a point of friction to contempt enforcement, but rather it eliminates it entirely for most existing federal injunctions.

In short, this bill would eliminate contempt enforcement for most previously granted preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders, and for all final injunctions issued by federal courts. These include not only injunctions in the past three months against federal defendants, but also injunctions stretching back years in corporate disputes and breach of contract actions and civil rights cases. And it would knock out contempt enforcement of all final injunctions won by the DOJ, SEC, and every other government agency, including injunctions that the federal government may be seeking now.

Thank you for your article. The provision encourages overt defiance of the court and violates separation of powers. Outrageous.

Great, but what’s the takeaway for a Fed Courts exam in two days….?