The Bullfight Poem: Further Inquiry

down the rabbit hole from the Atlantic to Life Magazine and more

Last week I wrote a brief and speculative post questioning whether the bullfight poem traditionally attributed to Domingo Ortega, translated by Robert Graves, was really composed by Ortega or was instead composed by Graves and attributed to Ortega for narrative value.

Recall, here’s the poem:

Bullfight critics ranked in rows

Crowd the enormous Plaza full;

But only one is there who knows

And he’s the man who fights the bull.

In brief, I asked:

Do we really believe that this poem can be attributed to Domingo Ortega, or is Graves actually telling a story for dramatic effect, and he’s really the one who came up with the poem?

Isn’t it somewhat unlikely that a famous matador happened to “remark the other day,” in Spanish, something that could be faithfully rendered into beautiful rhyming couplets? On the other hand, isn’t it more likely that Graves might have needed to put his own poem into the mouth of a matador because, well, he’s the man who fights the bull. It doesn’t work if it’s just a poet who says it!

I also pointed to a Time Magazine article from early 1961 that described a very similar verse as being composed by Graves on the spot “in three minutes flat.”

Thanks to all of you for your many emails and comments about this post. Your investigations and my own have revealed some more interesting things, and also pose some further puzzles.

What Did Domingo Ortega Say About Bullfighting?

Robert Graves did live in Spain and watch bullfighting, although my investigation of Graves’s papers so far does not reveal evidence that the two were personal friends. But Domingo Ortega did make a number of public pronouncements about bullfighting. Perhaps the most relevant is his January 1961 essay The Matador in the Atlantic. This essay was written the month before the Time Magazine story that first quotes the early version of Graves’s poem, so it’s an especially plausible source.

The closest thing in Ortega’s Atlantic essay to Graves’s poem is this passage:

The situation we are in today has come about because the aficionado has lost his knowledge of bulls, and the masses have not cared whether it was a bull, a cat, or a hare. The art of the bullfight is rooted in the danger presented by the bull. It this danger is removed — at any rate, for the person who is near the bull — the art of bullfighting no longer exists. The beauty, the nobility of the bullfight reside in the bullfighter’s experiencing, though also overcoming, the feeling that this is no joke and that he is not in the ring to hurt the bull by teasing it. It is then that the torero really lives and can create the sublime, spinechilling moments of his art.

This passage does have a couple of elements of Graves’s poem — a reference to the ignorance of bullfighting “aficianados” (who are “critics” in Graves’s poem) and a reference to the special understanding of the bullfighter. But I don’t think it really captures the same sentiment of expertise through practice instead of study. And regardless, it’s so far from the lyric of what Graves wrote that calling Graves’s poem a “translation” of Domingo’s remark is hilarious.

[As an aside, I am aware of the broad and fascinating debates about the nature of literary translation. What is it to translate Eugene Onegin? Must it be done quasi-literally, as Nabokov did, or rewritten as an English-language lyric with properties analogous to Onegin’s in Russian as Falen and Hofstadter attempted? How distant can the new work be from the original and still be a “translation”? Is Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus a translation of Ovid’s Philomela? Is Joyce’s Ulysses a “translation” of Homer’s Odyssey? Was T.S. Eliot right in his Nobel speech that this is a particularly insuperable problem for poetry? For Graves’s own thoughts on these questions, it turns out that you can read them in The Atlantic, in an essay called . . . “The Polite Lie.”]

An even closer match for the sentiment of the poem is when Ortega is quoted in this 1959 New York Times story (thanks Joe Camden), saying: “Many aficionados, but no experts. When am in the ring, only two of us know what is happening: the bull and myself." But for these indirect quotations we again have questions of translation — Ortega did not speak English so far as I can tell (his Atlantic essay was also translated) so this remark was translated into English by somebody else, such as the author of the story. And who was the author of the 1959 New York Times story? …. Robert Graves!

Where does Ortega end and where does Graves begin? How much of what we know about Ortega’s commentary on bullfighting has been filtered through the “polite lie” of Robert Graves? I am even less sure than when I started.

What about JFK?

As I mentioned earlier, the bullfight poem seems to have been popularized in America by President John F. Kennedy, who apparently used the poem during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy’s biographer, Sorensen, pointed the way to Graves’s claim to be reproducing an Ortega translation. I had assumed that Kennedy or one of his staffers had read Robert Graves’s book and that was how the Ortega/Graves poem made its way onto the President’s tongue.

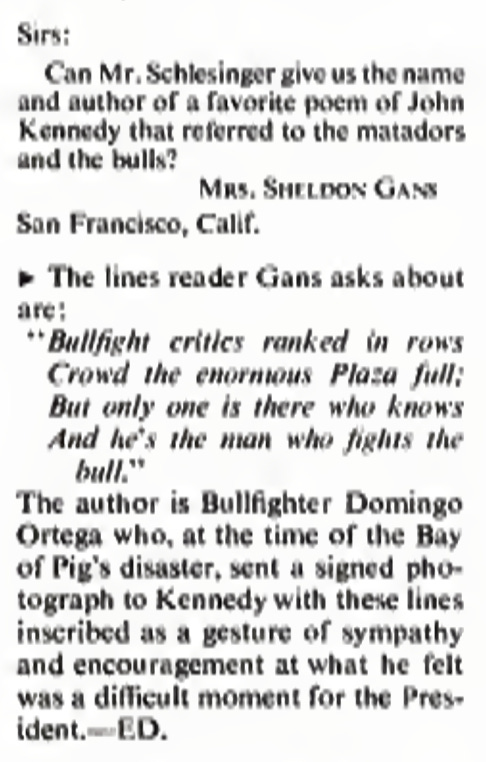

Then I found Life Magazine. In 1965, Life Magazine published an excerpt of Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s Thousand Days, about the Kennedy administration. This seems to have inspired a reader to ask him about the source of the bullfight poem. In the Aug. 6, 1965 issue, the following Q&A appears in the letters to the editor:

If this is true, if Ortega himself sent “a signed photograph to Kennedy with these lines,” that seems like a huge confirmation of the original story!

But. On this account did Ortega write the lines … in Spanish? In English? The Life account makes it sound as if the lines were written in English. But again, I have not yet seen evidence that Ortega wrote in English, and even those who claim that Ortega wrote the poem all seem to think Graves translated it. So is the idea that Ortega had taken Graves’s English translation of his alleged work, then copied it in English onto his own photograph, and sent it to President Kennedy? Stranger things have happened, but it’s a surprising thing to imagine.

And if this account is true, where is the photo? With the help of the amazing Chicago library staff, I started poking around the digitized finding aid for the JFK papers. So far I have found no sign of this supposed Ortega photo. (Let me know if you find it!)

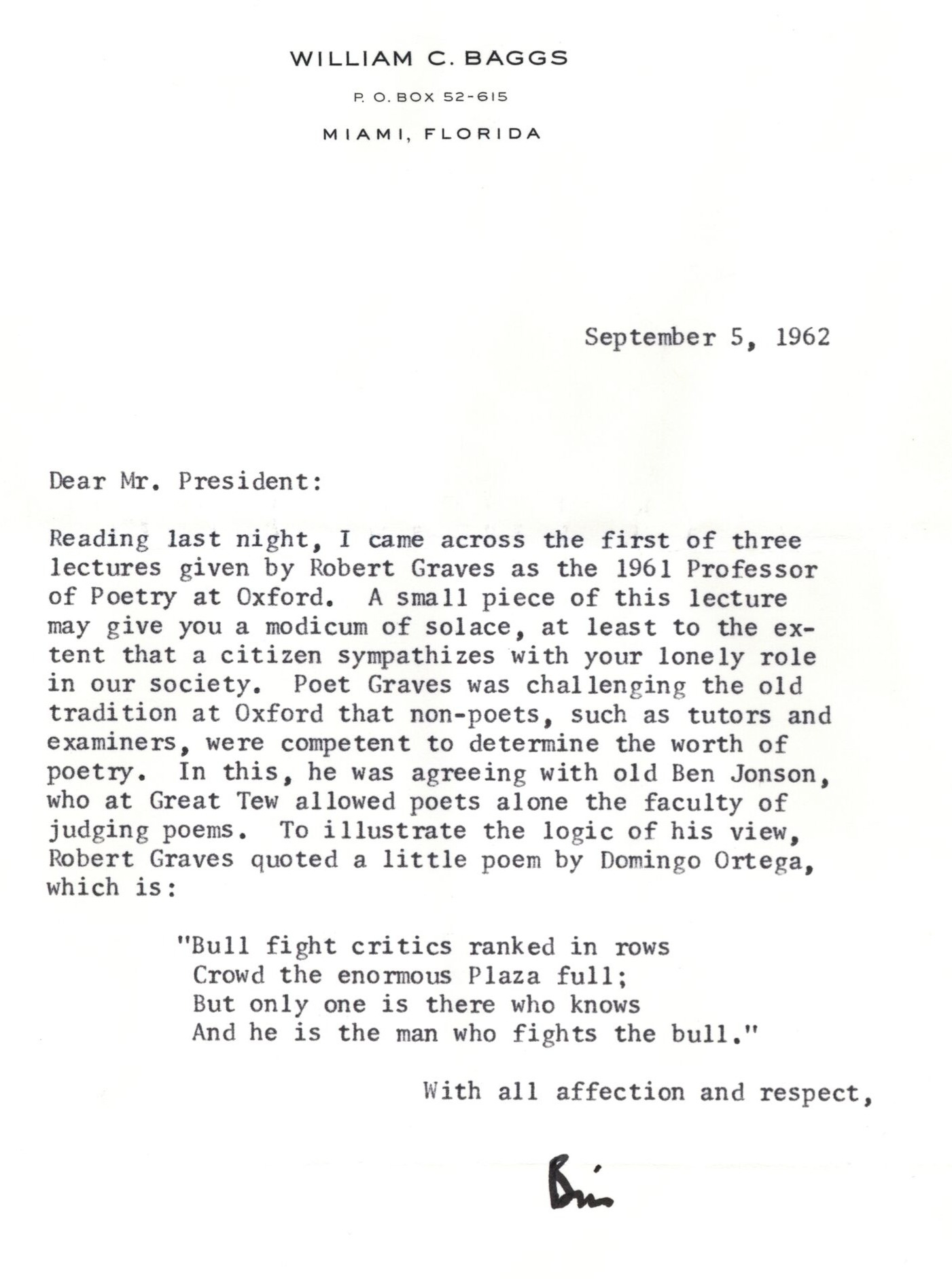

But one of our librarians, Keith Klein did find something else. In a folder described as: "materials maintained by President John F. Kennedy’s personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln," there is a 9/5/62 letter from William C. Baggs, who was apparently the editor of the Miami News and a friend of Kennedy’s.

Is this where Kennedy learned of the Graves/Ortega poem? If so, it seems consistent with the original hypotheses that Graves wrote a poem inspired by Ortega, passed it off as a poem composed by the matador, and now we’ve all come to accept Graves’s fictional author as the real author of the poem.

But then what the heck was the editor of Life magazine talking about?

If you'd like to read about a somewhat fictionalized version of Robert Graves, I would highly recommend the WWI historical fiction novel Regeneration. Graves makes the occasional appearance there since he was a close friend of Siegfried Sassoon. Sassoon's protest manifesto ("A Soldier's Declaration") sets the book and the overarching theme in motion, and it was Graves who saved him from being court-martialed and got him sent to Craiglockhart instead (a hospital for "shell-shocked" soldiers).