Remedies for a Constitutional Crisis

New paper by Baude, Bray, and Levy

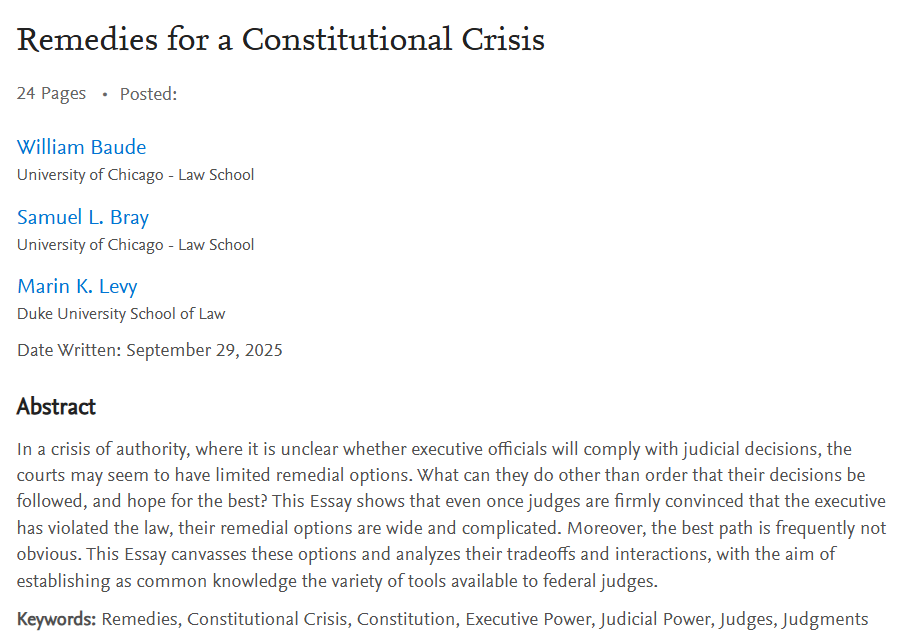

We have a new draft paper on SSRN, Remedies for a Constitutional Crisis, 139 Harv. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2026). Here’s the abstract:

In a crisis of authority, where it is unclear whether executive officials will comply with judicial decisions, the courts may seem to have limited remedial options. What can they do other than order that their decisions be followed, and hope for the best? This Essay shows that even once judges are firmly convinced that the executive has violated the law, their remedial options are wide and complicated. Moreover, the best path is frequently not obvious. This Essay canvasses these options and analyzes their tradeoffs and interactions, with the aim of establishing as common knowledge the variety of tools available to federal judges.

And the Introduction:

In a constitutional showdown with the executive branch, the courts may seem to have limited remedial options. To be sure, there are endless debates about what the law requires of the executive, how much deference the courts should give, and so on. But once we reach a point where courts conclude that the executive is violating the law, what can they do but order compliance? And what can we do but hope that the executive feels compelled to comply, whether by conscience or political forces?

Today, that compliance is hard to take for granted. Indeed, the risk is that the executive branch will blow off the judiciary, ignoring its judgments, refusing to obey its decrees, courting contempt, accusing judges of fictitious wrongdoing, tacitly encouraging retaliation against them, and elevating and appointing a yes-man to the bench. Indeed, there is evidence that this is what is happening.[1]

The upshot is that we are slipping into a crisis of judicial authority—what one could call a “constitutional crisis.” We use the phrase here reluctantly, for it is overused and vague. And we use it without knowing what will come next, and even though we might need a new word if things get worse. (It was called the “Cuban Missile Crisis,” even though it ended fine, and even though it could have gotten much worse, and even though we would have needed a new word for what happened if it did.) The phrase “constitutional crisis” at least captures the sense that the courts face an unusual challenge today, and that the precedents, such as they are, are not reassuring.[2] Call it what you will, it is not good.

What courts can do to enforce their decisions in such a crisis is the inquiry at the heart of this Essay. Suppose that in a particular case the courts are confident that the executive branch is acting and has acted unlawfully. What then? What do they do? If courts cannot simply assume that the executive will meekly accept their decisions, what options are open to the least dangerous branch? Do the federal courts have choices that will coax the executive branch into more law-abiding behavior? Or will those choices hasten the slide toward an equilibrium in which the executive acts contemptuously but escapes contempt? Do the federal courts have choices that will provide an effective resistance to law-breaking by the executive, shoring up the rule of law? Or will those choices merely accelerate and heighten the conflict between the branches, precipitating a battle that the judiciary can start but not win?

Our central claim is that the range of remedial options available to courts is broader than it may seem at first—and that the best path is not always obvious. Even when it is clear that the executive branch has acted unlawfully, it is not necessarily clear what courts can do about it. Even if we are in a crisis, and the choice of judicial response is very important, that does not make obvious the correct choice. We recognize that our readers will assess the risks associated with each option in various and varying ways, and that our own assessments may change as the world changes.[3] So this Essay does not attempt to crown any one choice as the right one. Nor do we claim that any of these remedial choices will be enough to avert or undo a constitutional crisis. They are not remedies in that sense.

Our aim is more modest: we will lay out the menu of options that are available to federal judges, highlighting the tradeoffs among them. But we recognize that we do not have the burden of choice, which belongs instead to the judges—and, we should acknowledge, to the president and the other executive officers and employees, as well as to the members of Congress. In every separation of powers crisis, and in every averted separation of powers crisis, the decisive decisions are not made by law professors:

Bullfight critics ranked in rows

Crowd the enormous Plaza full;

But only one is there who knows—

And he’s the man who fights the bull.[4]

[1] See, e.g., Daniel T. Deacon & Leah M. Litman, Legalistic Noncompliance, 75 Duke L. J. (forthcoming 2026) (draft of August 2025). For a contrary view, see Adrian Vermeule, Someone Is Defying the Supreme Court, but It Isn’t Trump, N.Y. Times (July 31, 2025).

[2] See generally Sanford Levinson & Jack M. Balkin, Constitutional Crises, 157 U. Pa. L. Rev. 707 (2009); Keith E. Whittington, Yet Another Constitutional Crisis, 43 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 2093 (2002); Arthur Bestor, The American Civil War as a Constitutional Crisis, 69 Am. Hist. Rev. 327 (1964).

[3] Judges might also derive wisdom from experiences around the world, though with the usual caveats about translating lessons from other institutions to ours. See, e.g., Benjamin Garcia-Holgado, Overruling the Executive: Judicial Strategies to Resist Democratic Erosion, 13 Journal of Law and Courts 274–303 (2025); Fortunato Musella & Luigi Rullo, Constitutional Courts in Turbulent Times, 25 European Politics and Society 461–467 (2024); and Jeffrey K. Staton, Christopher Reenock & Jordan Holsinger, Can Courts be Bulwarks of Democracy? Judges and the Politics of Prudence (2022).

[4] Poem attributed to Domingo Ortega by Robert Graves, in Robert Graves, Oxford Addresses on Poetry 4 (1962).

And the conclusion:

This Essay is an attempt to sketch a number of remedial options for the judiciary in a time of impending crisis. These options include questions of how and whether to strategize about executive behavior, about whether to push against or give back to the executive, about the internal structure of the judiciary, and about what the judiciary should do and what it should say.

Whatever answers judges give to these questions, we hope we have shown that they are complicated, reflecting tradeoffs, uncertainty, and institutional judgment. That fact helps for understanding the judiciary’s reaction to crisis. Because the correct remedial approach is so contestable, two judges can disagree profoundly about what their duties as a judge may require—whether with respect to contempt enforcement, appropriate judicial rhetoric, or the Supreme Court’s exercise of discretion about staying lower court decisions—even as they agree on both the legal merits and the larger constitutional picture. Therefore, one cannot easily say in every instance “if the court really recognized this was illegal, they would ___”; or “if the court really understood what was going on, they would ___.” One cannot say across the board “because the courts have not ordered ____, they do not understand what is happening.” Because the remedial choices are complicated and non-obvious, disagreement about them need not be a sign of ignorance or bad faith.

Indeed, our hope in making the range of options explicit is that we can make it easier for judges and others to come together—at least in understanding and articulating the tradeoffs they face, rather than hiding those tradeoffs behind unarticulated assumptions. Perhaps each judge and each lawyer already knows the choices we put forward here. Now we can all know them together.

I look forward to this. I wrote a celebrated Twitter thread about some of the remedies courts have to coerce presidents a few months ago.

https://x.com/dilanesper/status/1889448333854515430

See here for more remedies:

https://x.com/dilanesper/status/1914050441920549054