Reactions to the Smith & Wesson Oral Argument

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Smith & Wesson v. Estados Unidos Mexicanos. For those not already following it, the case concerns whether the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA) bars a suit by the Government of Mexico against firearms manufacturers alleging that the manufacturers are responsible for violence that occurs in Mexico involving illegally trafficked weapons. Will and I previewed the case on a recent episode of the podcast, but I thought I’d follow up on the case now that we have a better sense of what the Justices think. A few scattered observations below.

The Big Picture

First, my biggest overarching thought about the case before argument was that the legal issues were nuanced and Mexico has a plausible theory that its suit is not barred by the language of the statute—but that, nonetheless, there was just no way that the Court would actually let a suit like this go forward. The Court just isn’t going to let foreign countries come into U.S. courts and impose potentially crippling financial liability on American gun companies.

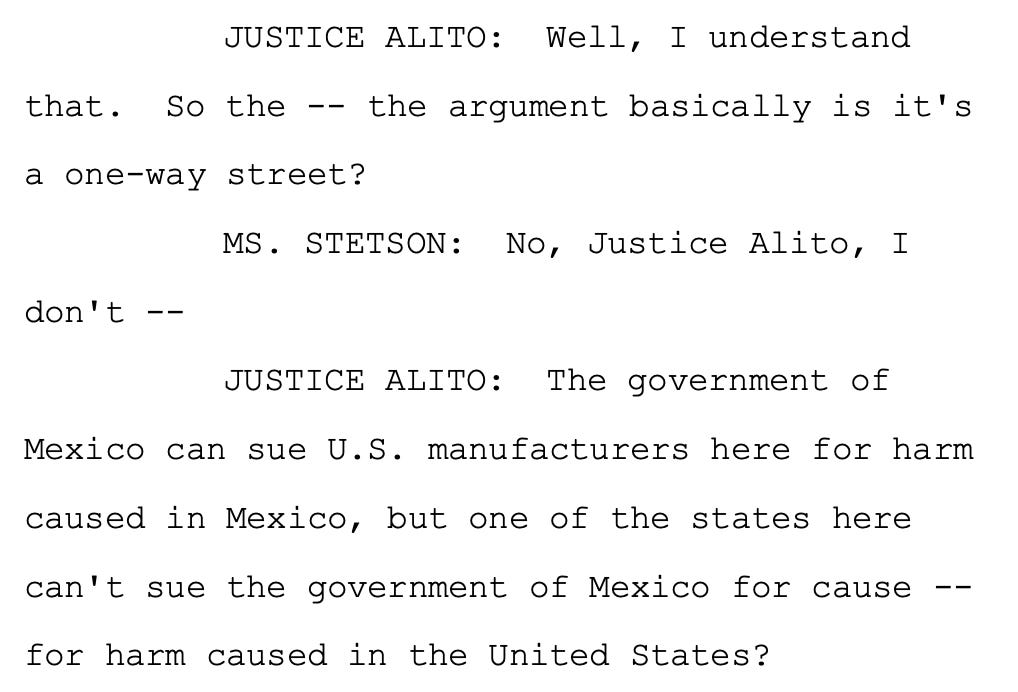

The argument didn’t change that prior. What did surprise me, however, was how openly Justice Alito made this point:

(a couple pages later)

So, whatever the “technical legal issues” in the case, as Justice Alito put it, the big picture seems likely to drive at least his vote in the case. I don’t think Justice Alito’s hypothetical is very well-taken given the fundamental difference between a sovereign as plaintiff and as defendant. It seems like the right question would be: if Mexican companies were making products that were causing harm in this country, could the United States sue them? It’s not obvious that the answer should be “no.”

Aiding and Abetting and the Common Law

An issue that I’ve been puzzling about for a long time (and plan to write about at greater length soon) is the role of common-law reasoning in the “general part” of the criminal law. Despite the frequent admonition that criminal law is supposed to be entirely statutory in order to protect separation-of-powers and due-process values, much of the “general part” of federal criminal law—the “the basic principles that govern the existence and the scope of liability” in Herbert Wechsler’s words—cannot be plausibly described as the product of statutory interpretation.

This observation is certainly true of federal aiding-and-abetting doctrine. As one example, consider Rosemond v. United States, which considered what was required to prove that a defendant aided and abetted the crime of "us[ing] or carr[ying]" a firearm "during and in relation to any crime of violence or drug trafficking crime." Justice Kagan’s opinion concluded that “[a]n active participant in a drug transaction has the intent needed to aid and abet a § 924(c) violation when he knows that one of his confederates will carry a gun”—but only where that knowledge is “advance knowledge . . .that enables him to make the relevant legal (and indeed, moral) choice.”

That rule cannot be found in the sparse language federal statute providing for aiding-and-abetting liability, 18 U.S.C. § 2. Instead, it’s the product of pretty free-wheeling, policy-based common-law-type rulemaking by the Court. (In an opinion joined by Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Roberts! How do formalists reconcile this kind of interpretation?)

Lots more I could say about that, but for now that’s just setup to talk about another point in oral argument. Mexico’s theory in the case is that PLCAA doesn’t apply under an exception for suits alleging that “a manufacturer or seller of a qualified product knowingly violated a State or Federal statute applicable to the sale or marketing of the product, and the violation was a proximate cause of the harm for which relief is sought, including . . .any case in which the manufacturer or seller aided, abetted, or conspired with any other person to sell or otherwise dispose of a qualified product, knowing, or having reasonable cause to believe, that the actual buyer of the qualified product was prohibited from possessing or receiving a firearm or ammunition . . . .”

One big issue in the case is proximate causation—itself a concept that the Court fleshes out not with a dictionary but with common law sources like the Restatements. For now, though, I’m interested in the part of the case that concerns whether the defendants can be said to have aided and abetted unlawful sales by firearms retailers.

Justice Jackson asked some questions about how to interpret the scope of aiding and abetting under PLCAA:

A little later:

Noel Francisco, the gun manufacturers’ counsel, seemed a little unsure about where Justice Jackson was going with this point. She returned to it later, saying she found it “odd to me that suddenly a common law of aiding-and-abetting liability is coming in” when “what we're really doing is trying to understand what Congress intended with respect to the exception that it put in this statute.”

I found this line of questioning a bit puzzling, too. PLCAA doesn’t provide its own definition of aiding and abetting, and it’s hard to see how the Court could develop a PLCAA-specific theory of aiding and abetting without more to go on from the statute. Whatever one thinks about the legitimacy of the larger project of fleshing out vague phrases like aiding and abetting using common-law reasoning, it seems like that language in PLCAA should probably mean the same thing it means in other federal statutes. The Court in Twitter v. Taamneh, which interpreted “aids and abets” in a different federal statute, applied the presumption that such a common-law phrase carried the “old soil” with it.

What to Hope For

I don’t have particularly strong views on what the right outcome in the case is. I think Mexico has a (perhaps surprisingly) plausible argument on the text. But it’s also hard to shake the feeling that this just is exactly the kind of thing that Congress would have wanted to stop with PLCAA.

What I do hope for, though, is that the Court doesn’t say anything that could unintentionally cause damage to other areas of the law. Precisely because common-law reasoning drives so much of the interpretation of concepts like aiding and abetting, whatever the Supreme Court says about that question is likely to have significant ripple effects. Not just on federal criminal law, but also on state criminal law (and likely tort law, too). Supreme Court opinions have a big gravitational pull. So I’d be concerned about the danger that the Court accidentally says something about aiding and abetting here that’s more sweeping than the Justices realize. (And perhaps this fear is driving Justice Jackson’s apparent interest in a PLCAA-interpretation, though I think any opinion will have that gravitational pull on state courts even if the Court’s analysis is ostensibly limited to the PLCAA context).

Aiding and abetting liability usually requires intent or purpose: the accessory has to aid the principal’s criminal conduct with the intent of helping the criminal conduct succeed. But a perpetual problem involves those who sell products or services to people using those products or services for criminal ends. Drug manufacturers who sell drugs to someone who is reselling them illegally. Chemicals manufacturers whose products are precursors to illegal drugs. And so on. The problem is that often the seller knows that the buyer is using the product for illegal purposes, but knowledge doesn’t necessarily mean (and shouldn’t necessarily mean) intent. Home Depot shouldn’t be guilty of methamphetamine manufacturing even if it knows with certainty that some small percentage of its customers are wanna-be Walter Whites. But some sellers really do seem sufficiently culpable that they deserve responsibility for the criminal acts that they make possible.

For that reason, courts have developed various rules of thumb for when “knowledge-plus” can be rounded up to intent. A famous case, People v. Lauria, 251 Cal. App. 23 471 (1967), came up with the following test:

1. Intent may be inferred from knowledge, when the purveyor of legal goods for illegal use has acquired a stake in the venture. . . .

2. Intent may be inferred from knowledge, when no legitimate use for the goods or services exists.

3. Intent may be inferred from knowledge, when the volume of business with the buyer is grossly disproportionate to any legitimate demand, or when sales for illegal use amount to a high proportion of the seller’s total business. . . .

Lauria also suggested that for certain “serious crime[s]” such as murder, knowledge, rather than intent, would be sufficient.

Although Lauria is a state case, it draws heavily on U.S. Supreme Court cases, including Direct Sales, a case that the parties in Smith & Wesson spend a lot of time debating (and which Francisco conceded was Mexico’s “best case”). Although, again, one can question whether judge-made rules like this are best practices when interpreting federal criminal statutes, I’d submit that the Lauria test is a pretty good attempt to draw a line between ordinary commercial activity and criminal conduct. Considered in that light, Rosemond is just one more case trying to carefully draw a culpability distinction that treads the line between purpose and knowledge.

The Court is (understandably) not as dialed into aiding and abetting liability as 1L crim profs are. But I noted that Justice Gorsuch repeatedly suggested that under Rosemond, the standard for aiding and abetting is “intent.” I don’t think that’s quite right as to Rosemond itself, but more generally it’s not quite right with respect to aiding and abetting liability as a whole. Given that the Court may not have deeply engaged with the question, my hope is that any eventual opinion in Smith & Wesson steers clear of broad pronouncements that could have an unintended effect well beyond the PLCAA context.